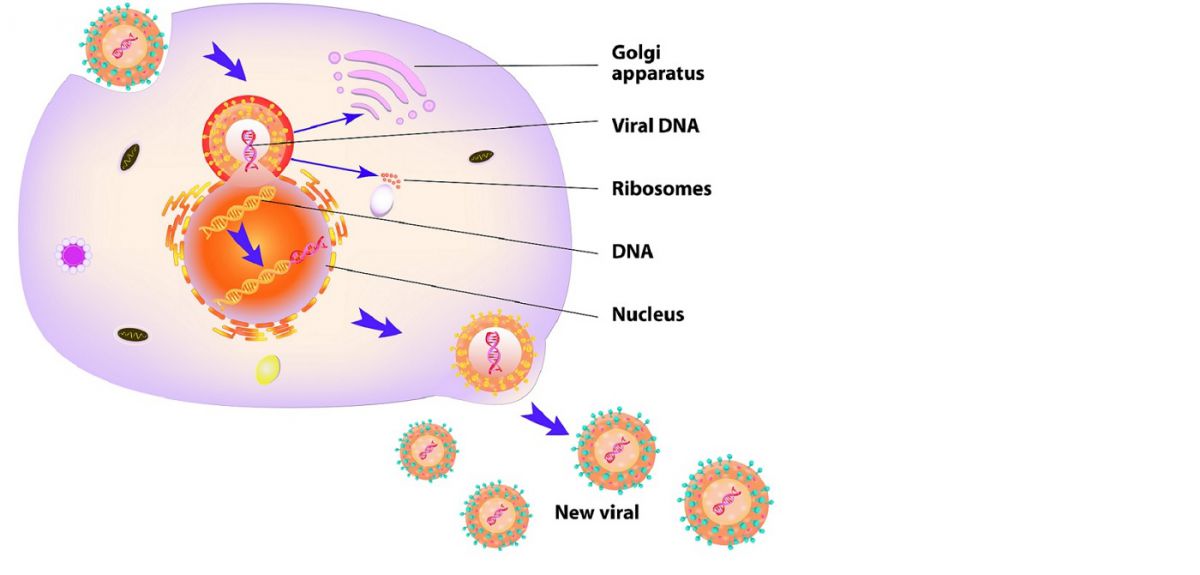

Source: designua via Shutterstock

Researchers discover immune system’s 'Trojan Horse'

Oxford University researchers have found that human cells use viruses as Trojan horses, transporting a messenger that encourages the immune system to fight the very virus that carries it. The discovery could have implications for the design of new vaccines.

Scientists already knew that when a virus containing or producing DNA enters a cell in the body it is detected by a protein called cGAS. This in turn produces a small signalling molecule called cGAMP which acts as what’s known as a second messenger, activating other elements of the body's immune response. Now, the Oxford team have discovered that as some viruses replicate, they incorporate cGAMP, meaning that as they infect new cells the cGAMP immediately prompts an immune response.

Professor Jan Rehwinkel from the MRC Human Immunology Unit, within Oxford University’s Radcliffe Department of Medicine, explained: 'We hypothesised that as the virus replicated, cGAMP was incorporated and carried to the next cell to be infected. This may not have been spotted before because in the lab researchers tend to use cells that are free of cGAS and therefore unable to produce cGAMP.

'By putting cGAS back into some of these cells, we were able to compare what happened as the virus moved to infect new cells. Viruses from cells that had been loaded with cGAS and could produce cGAMP stimulated a much more potent immune response when they moved into new cells than viruses that had come from cells without cGAS.

'This confirmed our hypothesis in cells with artificially high levels of cGAS but we needed to also test it using cells with naturally occurring levels of the protein. We used cells from mice and compared these to cells from genetically engineered mice that were cGAS free. The finding was the same – where cGAMP was produced, it travelled within the virus particles.

'It is not yet clear whether cells are tagging these virus particles deliberately or whether it is simply a by-product of how viruses replicate.'

The Oxford team are now investigating whether the research could be used to improve a class of vaccines. Viral vectored vaccines are genetically engineered virus particles designed to prompt an immune response against particular diseases. The researchers will look at whether by loading these particles with cGAMP it is possible to stimulate a bigger immune response, making such vaccines more effective.

The paper describing this research, Viruses transfer the antiviral second messenger cGAMP between cells, is published in Science Express.

Similar results have been obtained by a group of scientists led by Professor Nicolas Manel at the Institut Curie, Paris, and will be published simultaneously.

cGAMP’s role in the immune response

1. cGAS (Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase) detects viruses containing or producing DNA and in turn produces cGAMP.

2. cGAMP (Cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate) binds to STING (Stimulator of interferon genes).

3. STING drives production of type I interferons, which regulate the immune system’s response to virus infection.

Friedreich’s Ataxia research collaboration announced

Friedreich’s Ataxia research collaboration announced

Researchers discover immune system’s 'Trojan Horse'

Researchers discover immune system’s 'Trojan Horse'

Brown dwarf boasts 'Northern Lights'

Brown dwarf boasts 'Northern Lights'

Chimps use clay to detox and as a mineral supplement

Chimps use clay to detox and as a mineral supplement